Definition of Wind Energy

Wind energy is a form of renewable energy that is generated by converting the kinetic energy of moving air into usable electrical power. This conversion is achieved using wind turbines, which capture the wind’s motion through rotating blades and transform it into mechanical energy. The mechanical energy is then converted into electricity by a generator. Wind energy is clean, sustainable, and produces no direct greenhouse gas emissions, making it an important alternative to fossil fuel-based power generation.

Fundamentals of Wind Energy Conversion

The conversion of wind energy into electrical energy is based on the principle of extracting kinetic energy from moving air. When wind flows across the blades of a wind turbine, aerodynamic forces cause the blades to rotate. This rotational motion turns a shaft connected to a generator, producing electricity.

The amount of power available from wind depends on three main factors: wind speed, air density and the swept area of the turbine blades. Wind speed is the most critical factor, as the power generated increases with the cube of the wind speed. However, only a portion of the wind’s energy can be converted into useful power due to physical and aerodynamic limitations, such as the Betz limit, which defines the maximum theoretical efficiency of a wind turbine.

Efficient wind energy conversion also requires proper turbine design, optimal blade shape, suitable site selection and advanced control systems to maximize energy capture while ensuring safe and reliable operation.

Betz Limit

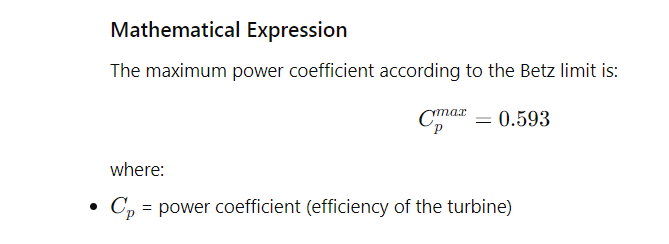

The Betz limit is a fundamental principle in wind energy that defines the maximum theoretical efficiency of a wind turbine. It states that no wind turbine can convert more than 59.3% of the kinetic energy in wind into mechanical energy.

This limit was introduced in 1919 by the German physicist Albert Betz.

In Simple Terms, The Betz limit means that a wind turbine can never capture all the energy in the wind, and 59.3% is the absolute maximum that can theoretically be extracted.

Explanation

When wind passes through a turbine, the air must continue to move downstream after energy extraction. If a turbine were to capture all the wind’s energy, the air behind it would stop completely, preventing more wind from flowing through the rotor. To maintain continuous airflow, only part of the wind’s kinetic energy can be extracted, which leads to the Betz limit.

Importance of the Betz Limit

- It provides a theoretical upper bound for wind turbine efficiency

- Helps engineers evaluate and compare turbine performance

- Guides the design of blades and turbine systems

- Explains why real turbines typically achieve efficiencies of 35–45%

In real-world conditions, losses due to blade drag, mechanical friction, electrical inefficiencies, and environmental factors reduce the achievable efficiency below the Betz limit. However, modern wind turbines are designed to operate as close to this limit as possible.

Types of Wind Turbines and Their Applications

Wind turbines are classified based on the orientation of their axis of rotation and their intended use. Each type is designed for specific wind conditions, locations, and power requirements.

1. Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines (HAWT)

Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines have their rotor shaft aligned horizontally, parallel to the ground. They are the most commonly used turbines worldwide.

Applications:

- Large-scale onshore wind farms

- Offshore wind power plants

- Utility-scale electricity generation

Advantages:

- High efficiency

- Proven and reliable technology

- Suitable for high-wind regions

2. Vertical Axis Wind Turbines (VAWT)

Vertical Axis Wind Turbines have a vertical rotor shaft and can capture wind from any direction without yaw mechanisms.

Applications:

- Urban and residential areas

- Rooftop installations

- Locations with turbulent or variable wind

Advantages:

- Omnidirectional wind capture

- Easier maintenance at ground level

- Compact design

3. Darrieus Wind Turbines

A type of VAWT with curved, airfoil-shaped blades resembling an eggbeater.

Applications:

- Small-scale power generation

- Experimental and hybrid energy systems

Advantages:

- Higher efficiency than other VAWTs

- Lightweight blade design

4. Savonius Wind Turbines

Another type of VAWT that uses drag force instead of lift.

Applications:

- Low-power applications

- Battery charging

- Water pumping

Advantages:

- Operates at low wind speeds

- Simple and robust construction

5. Onshore Wind Turbines

Installed on land in areas with strong and consistent wind flow.

Applications:

- Grid-connected electricity generation

- Rural electrification

Advantages:

- Lower installation cost

- Easier maintenance

6. Offshore Wind Turbines

Installed in seas or oceans where wind speeds are higher and more consistent.

Applications:

- Large-scale renewable energy production

- National power grids

Advantages:

- Higher power output

- Minimal land use impact

7. Small Wind Turbines

Designed for individual homes, farms, or small businesses.

Applications:

- Residential power supply

- Remote or off-grid locations

Advantages:

- Reduces dependence on grid electricity

- Suitable for decentralized energy systems

8. Medium Wind Turbines

Used for community-scale or commercial power needs.

Applications:

- Schools, factories, and villages

- Hybrid renewable energy systems

9. Large Wind Turbines

High-capacity turbines used in wind farms.

Applications:

- Utility-scale electricity generation

- National renewable energy targets

10. Floating Wind Turbines

Installed on floating platforms in deep-water offshore locations.

Applications:

- Deep-sea offshore wind farms

- Areas unsuitable for fixed foundations

Advantages:

- Access to strong deep-water winds

- Expands offshore wind potential

Different types of wind turbines are designed to meet diverse energy needs, ranging from small residential applications to large offshore power plants. The choice of turbine depends on wind conditions, location, power demand, and economic considerations.

Key Components of a Wind Energy System

A wind energy system consists of several integrated components that work together to convert the kinetic energy of wind into usable electrical power. Each component plays a critical role in ensuring efficient, safe, and reliable operation.

1. Rotor Blades

Rotor blades are aerodynamic structures designed to capture wind energy and convert it into rotational motion. Their shape and length determine how effectively the turbine extracts energy from the wind. Modern blades are made from lightweight composite materials to maximize strength and performance.

2. Hub

The hub connects the rotor blades to the main shaft of the turbine. It transfers the rotational force from the blades to the drivetrain while allowing blade pitch adjustment to control power output and protect the turbine during high wind conditions.

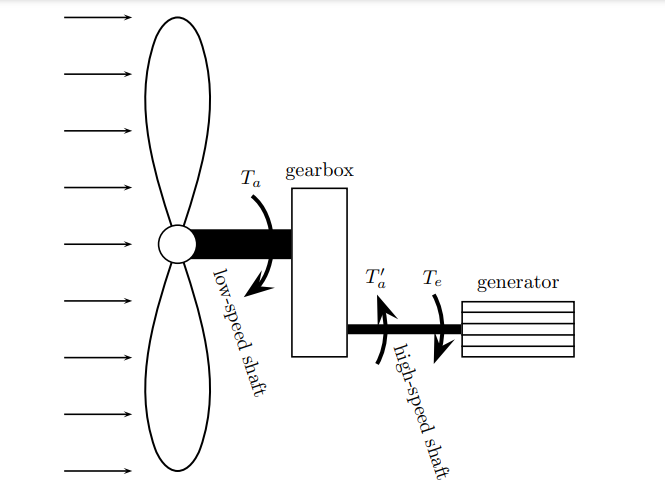

3. Main Shaft (Low-Speed Shaft)

The main shaft carries the rotational energy from the rotor to the gearbox. It rotates at a relatively low speed but transmits high torque, making it a crucial mechanical link in the system.

4. Gearbox

The gearbox increases the rotational speed from the low-speed shaft to a level suitable for electricity generation. Although some modern turbines use direct-drive systems, gearboxes remain common due to their efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

5. Generator

The generator converts mechanical energy into electrical energy using electromagnetic induction. Depending on the turbine design, generators may produce alternating current (AC) or direct current (DC), which is later conditioned for grid compatibility.

6. Nacelle

The nacelle is the protective housing mounted on top of the tower. It contains critical components such as the gearbox, generator, brake system, and control electronics, shielding them from environmental conditions.

7. Yaw System

The yaw system rotates the turbine so that the rotor faces the wind direction. Proper alignment with the wind ensures maximum energy capture and reduces mechanical stress on the turbine structure.

8. Pitch Control System

The pitch control system adjusts the angle of the rotor blades in response to changing wind speeds. This helps regulate power output, improve efficiency, and prevent damage during strong winds.

9. Tower

The tower supports the turbine and elevates it to higher altitudes where wind speeds are stronger and more consistent. Taller towers generally result in greater energy production.

10. Power Electronics and Control System

Power electronics regulate voltage, frequency, and power quality before electricity is supplied to the grid or local loads. The control system continuously monitors turbine performance and safety parameters, ensuring stable and efficient operation.

Aerodynamics and Blade Design Principles

Aerodynamics and blade design are fundamental to the performance and efficiency of wind turbines. The ability of a turbine to extract energy from wind depends largely on how well its blades interact with airflow and convert wind energy into rotational motion.

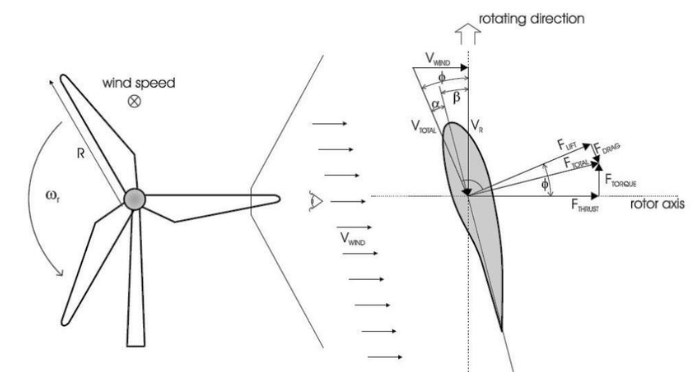

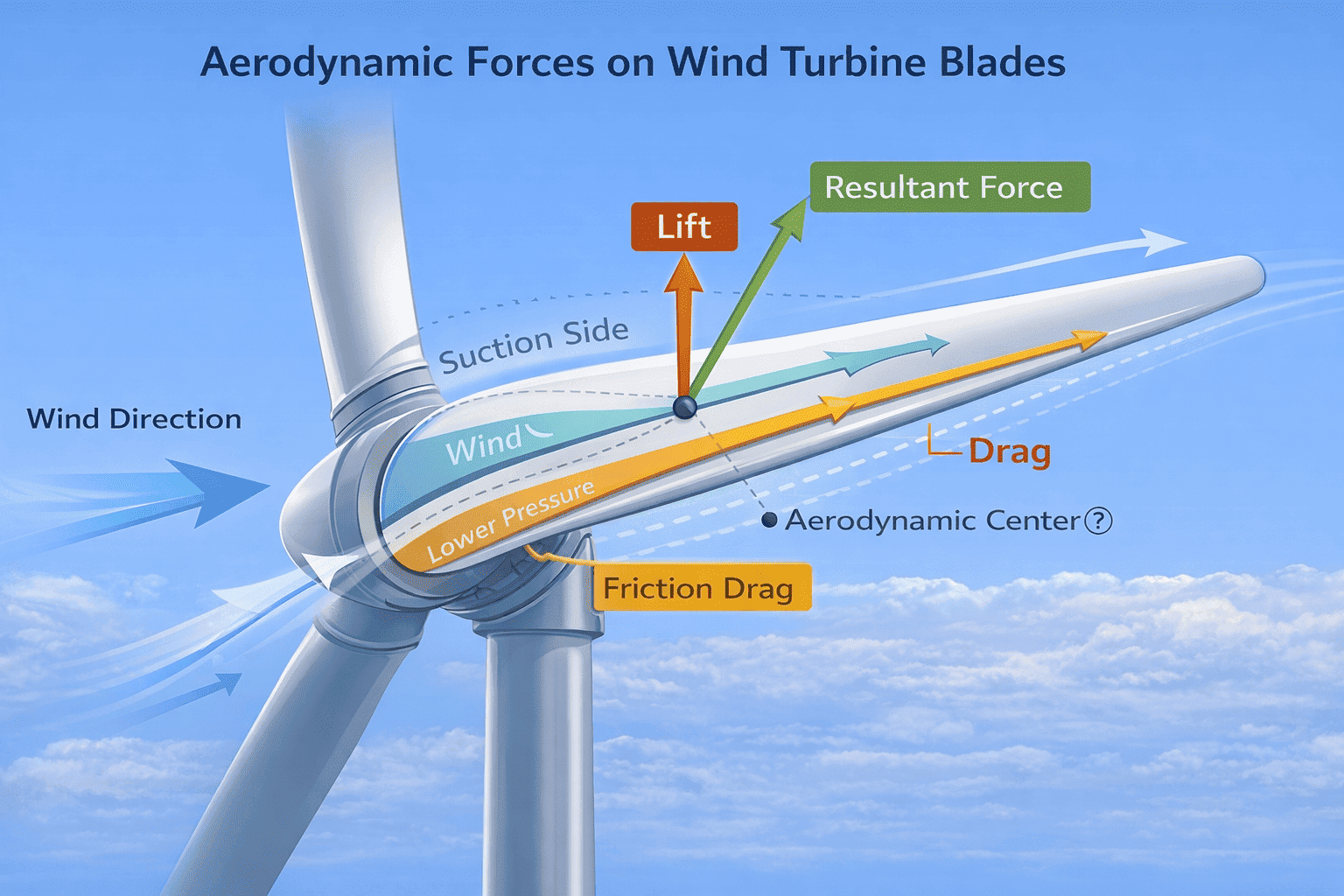

1. Aerodynamic Forces on Wind Turbine Blades

Wind turbine blades operate primarily on the principle of lift, similar to aircraft wings. When wind flows over the blade’s airfoil shape, a pressure difference is created between the upper and lower surfaces. This pressure difference generates lift, causing the blade to rotate. Drag forces also act on the blade but are minimized through careful aerodynamic design to improve efficiency.

Wind turbine blades extract energy from the wind through carefully controlled aerodynamic forces. These forces arise when moving air interacts with the blade’s airfoil shape, creating pressure differences and directional forces that cause the rotor to turn.

Lift Force

Lift is the primary force responsible for rotating the wind turbine. As wind flows over the curved surface of the blade, air moves faster on one side than the other, creating a pressure difference. This difference generates a force perpendicular to the direction of the wind. Lift pulls the blade forward along its circular path, producing rotational motion that drives the generator. Efficient turbine operation depends on maximizing lift while maintaining stable airflow over the blade surface.

Drag Force

Drag acts in the same direction as the wind flow and resists blade motion. It is caused by air friction and pressure losses around the blade surface. While drag cannot be eliminated entirely, modern blade designs aim to minimize drag because excessive drag reduces efficiency and increases structural stress. A well-designed blade generates much more lift than drag, ensuring smooth and efficient rotation.

Resultant Aerodynamic Force

The combined effect of lift and drag produces a resultant force acting on the blade. This force can be resolved into two components: one that contributes to rotor rotation (tangential force) and another that applies stress to the turbine structure (axial force). The tangential component is responsible for power generation, while the axial component influences tower and foundation design.

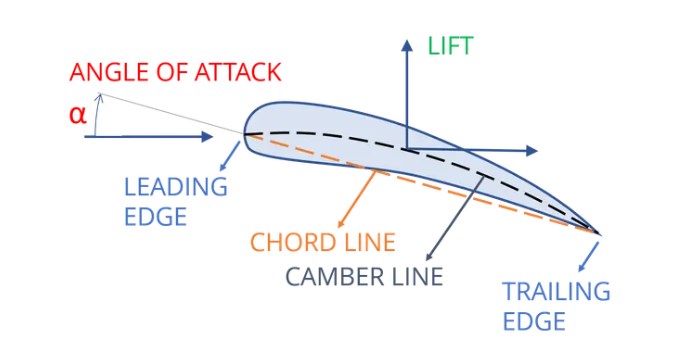

Angle of Attack

The angle of attack is the angle between the incoming wind direction and the blade’s chord line. It plays a crucial role in determining the magnitude of lift and drag. A small, optimal angle of attack maximizes lift and minimizes drag. If the angle becomes too large, airflow separates from the blade surface, causing aerodynamic stall and a sharp drop in performance.

Pressure Distribution on the Blade

As wind passes over the blade, low pressure develops on one side and higher pressure on the other. This pressure imbalance is not uniform along the blade length; it varies from the root to the tip due to changes in wind speed and blade geometry. Designers account for this variation by shaping and twisting the blade to maintain efficient force generation.

Tip Speed Ratio and Force Balance

The aerodynamic forces depend on the relationship between blade tip speed and wind speed, known as the tip speed ratio. At optimal ratios, aerodynamic forces are aligned to maximize rotational energy while minimizing vibration, noise, and fatigue loading.

Aerodynamic Stability and Control

To maintain safe and efficient operation under changing wind conditions, turbines use pitch control and yaw systems. These systems adjust blade orientation to regulate aerodynamic forces, preventing excessive loads during high winds and maintaining steady power output.

Aerodynamic forces on wind turbine blades are the foundation of wind energy conversion. By carefully controlling lift, drag, and force distribution through advanced blade design and control systems, wind turbines can operate efficiently, safely, and close to their theoretical performance limits.

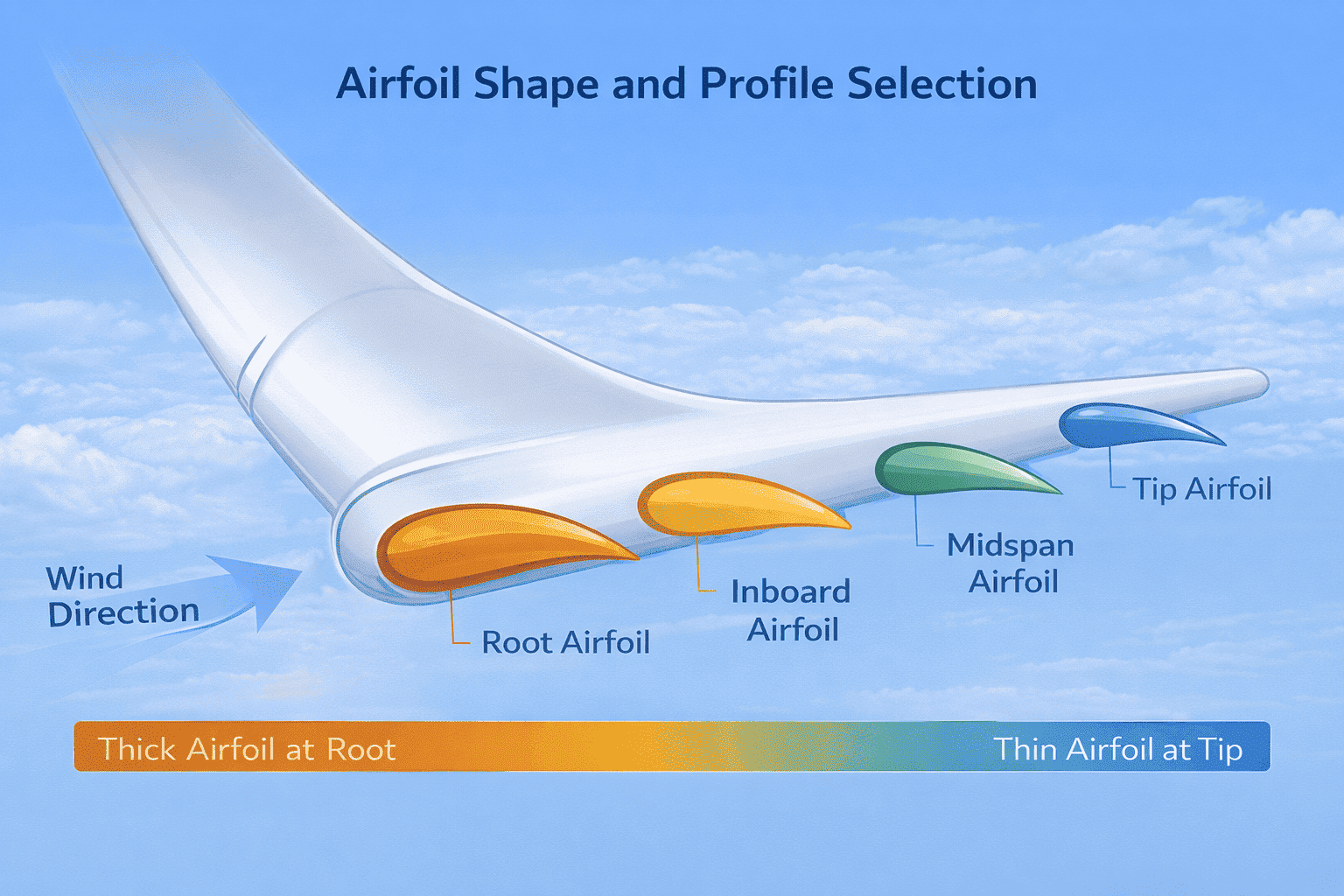

2. Airfoil Shape and Profile Selection

The cross-sectional shape of a blade, known as the airfoil, is designed to maximize lift while minimizing drag. Different airfoil profiles are used along the blade length to accommodate varying wind speeds and rotational velocities. Thicker airfoils near the root provide structural strength, while thinner profiles near the tip enhance aerodynamic performance.

Airfoil shape and profile selection are critical aspects of wind turbine blade design, as they directly influence how efficiently wind energy is converted into rotational motion. An airfoil is the cross-sectional shape of a blade, and even small variations in its geometry can significantly affect turbine performance, stability, and durability.

Purpose of the Airfoil in Wind Turbines

The primary function of an airfoil is to generate lift while minimizing drag. When wind flows around the curved airfoil surface, differences in air pressure are created, producing a lifting force that drives blade rotation. Unlike aircraft wings, wind turbine airfoils must perform efficiently over a wide range of wind speeds and angles of attack.

Variation of Airfoil Profiles Along the Blade

Wind turbine blades do not use a single airfoil shape throughout their length. Near the blade root, thicker airfoil profiles are selected to provide structural strength and accommodate internal components. Toward the blade tip, thinner and more aerodynamically refined profiles are used to reduce drag and improve energy capture at higher rotational speeds.

Lift-to-Drag Ratio Optimization

A key criterion in airfoil selection is the lift-to-drag ratio. High lift ensures effective energy extraction, while low drag reduces aerodynamic losses. Engineers choose airfoil profiles that maintain a high lift-to-drag ratio even under varying wind conditions, ensuring stable and efficient operation.

Performance at Different Reynolds Numbers

Wind turbine blades operate under a wide range of Reynolds numbers due to changes in wind speed and blade radius. Airfoil profiles are selected to perform well under these varying flow conditions, maintaining smooth airflow and minimizing flow separation across different operating regimes.

Stall Characteristics and Control

The stall behavior of an airfoil is a critical safety consideration. A well-designed airfoil exhibits gradual stall characteristics rather than abrupt flow separation. This allows turbines to maintain controlled operation and reduces mechanical stress during high wind speeds or sudden gusts.

Surface Sensitivity and Environmental Effects

Airfoil profiles are also chosen based on their sensitivity to surface roughness caused by dust, insects, or ice. Robust airfoil designs maintain acceptable performance even when surface conditions are not ideal, which is essential for long-term outdoor operation.

Material and Manufacturing Constraints

Airfoil selection must align with manufacturing capabilities and material limitations. Composite materials used in modern blades require airfoil shapes that can be reliably produced while maintaining aerodynamic accuracy and structural integrity.

Airfoil shape and profile selection are fundamental to wind turbine efficiency, reliability, and lifespan. By carefully tailoring airfoil geometry along the blade length and optimizing performance across varying wind conditions, designers ensure maximum energy capture while maintaining structural safety and long-term durability.

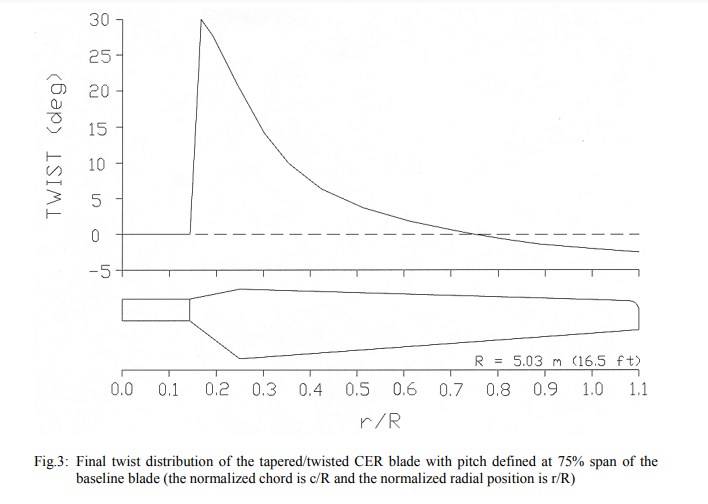

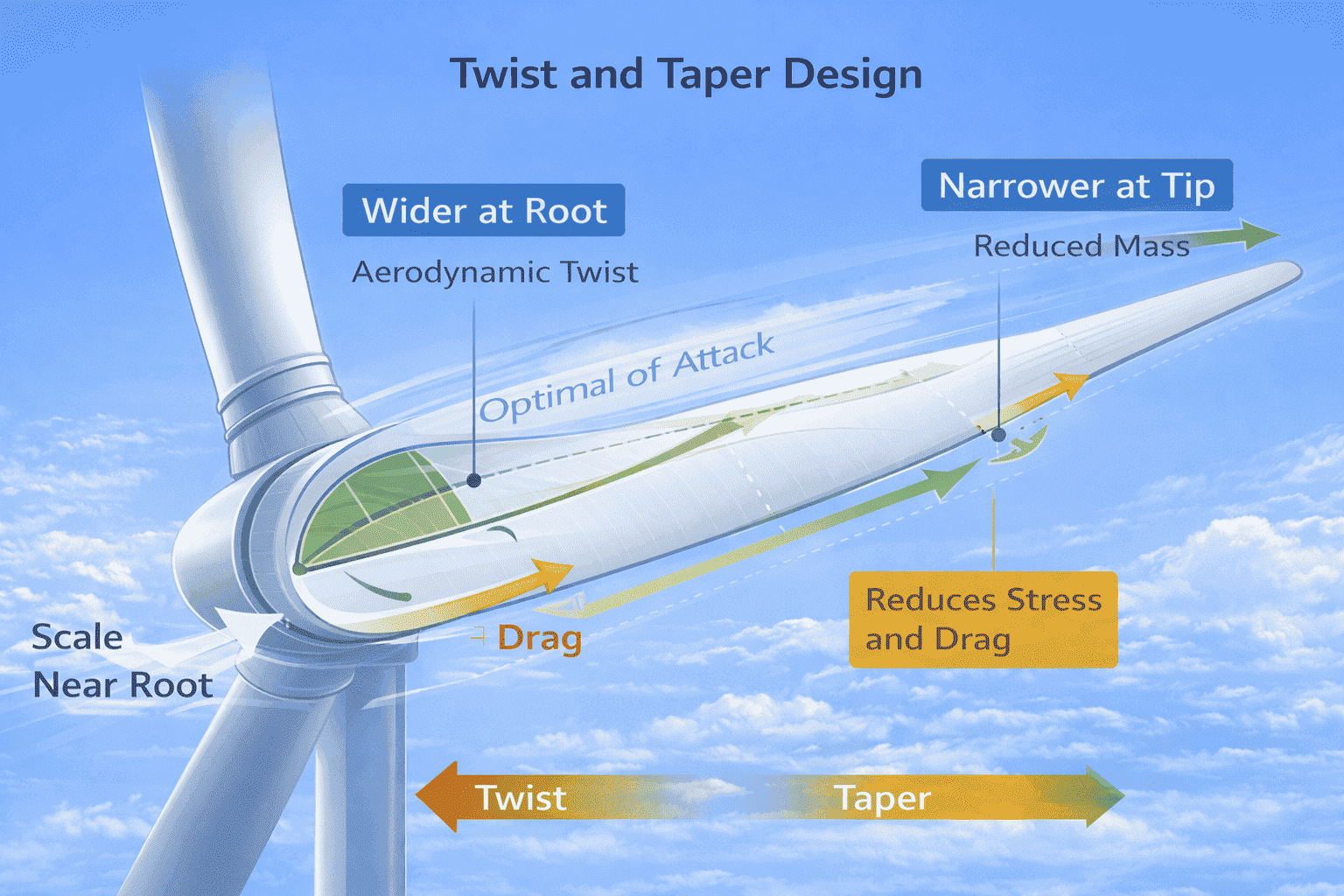

3. Twist and Taper Design

Twist and taper design are essential geometric features of wind turbine blades that ensure efficient energy extraction and structural reliability. Because wind speed, airflow direction, and rotational velocity vary along the blade length, a uniform blade shape would lead to poor aerodynamic performance. Twist and taper are applied to adapt the blade geometry to these changing conditions.

Wind speed and rotational speed vary along the length of the blade. To maintain an optimal angle of attack at every section, blades are designed with a gradual twist from root to tip. Tapering, where blade width decreases toward the tip, helps reduce aerodynamic losses and structural weight.

Purpose of Blade Twist

Blade twist refers to the gradual change in the blade’s angle from the root to the tip. Near the hub, the blade rotates more slowly and experiences different airflow conditions than at the tip. To maintain an optimal angle of attack along the entire blade, the root section is designed with a higher pitch angle, while the tip is more finely angled. This twist ensures that each blade section operates efficiently and contributes evenly to power generation.

Aerodynamic Benefits of Twisting

By maintaining a consistent angle of attack, blade twist prevents airflow separation and reduces aerodynamic losses. Without twist, only a small portion of the blade would operate at peak efficiency, while the rest would produce less lift or experience stall. Proper twisting improves overall lift distribution and increases energy capture across a wide range of wind speeds.

Purpose of Blade Taper

Taper refers to the gradual reduction in blade width from root to tip. The blade root is wider to provide mechanical strength and withstand high bending loads. As the blade extends outward, the width decreases to reduce aerodynamic drag and blade mass. This design improves efficiency while lowering structural stress.

Structural and Load Distribution Advantages

Tapered blades help distribute aerodynamic and gravitational loads more evenly along the blade. Reducing mass toward the tip lowers centrifugal forces and minimizes fatigue, extending blade lifespan and improving turbine reliability.

Noise and Efficiency Considerations

A tapered and twisted blade reduces tip turbulence and aerodynamic noise. Lower noise levels are particularly important for onshore turbines near populated areas. Additionally, smoother airflow along the blade enhances efficiency and reduces vibration.

Manufacturing and Material Optimization

Twist and taper designs are optimized to balance aerodynamic performance with manufacturing feasibility. Composite materials allow complex blade geometries to be produced accurately while maintaining strength and flexibility.

Twist and taper design enable wind turbine blades to adapt to varying aerodynamic conditions along their length. By optimizing airflow, reducing structural loads, and improving efficiency, these design features play a vital role in maximizing energy output and ensuring long-term turbine performance.

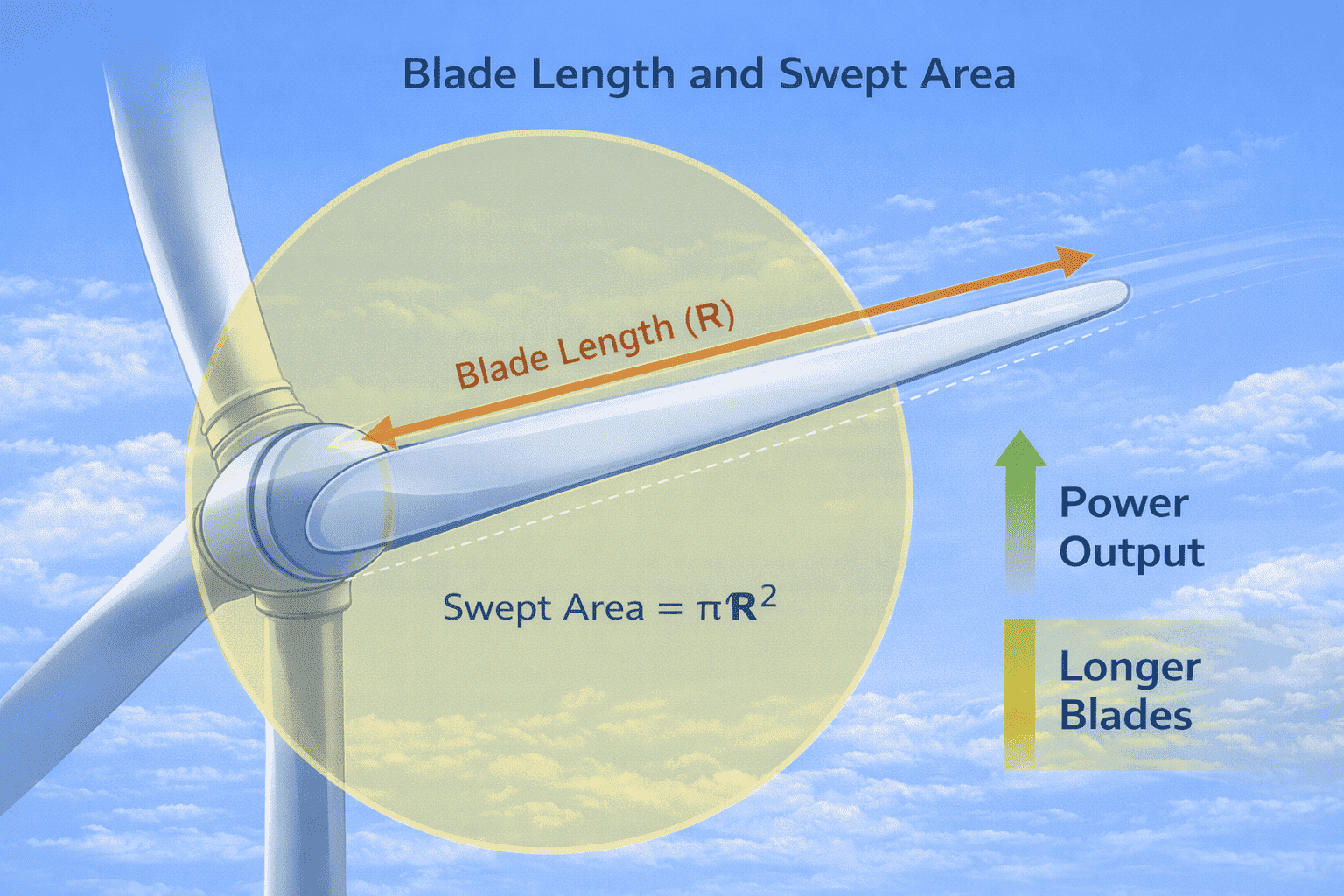

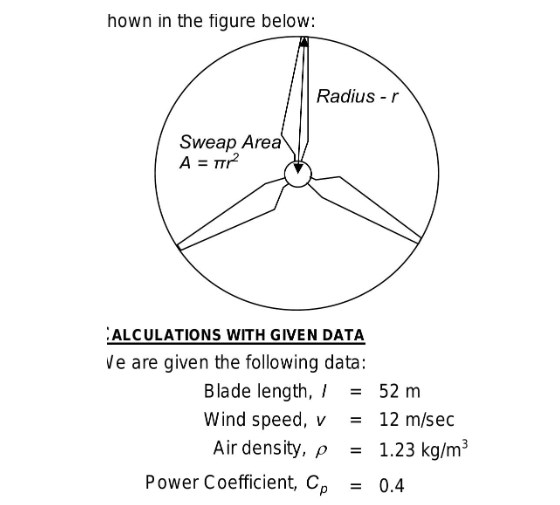

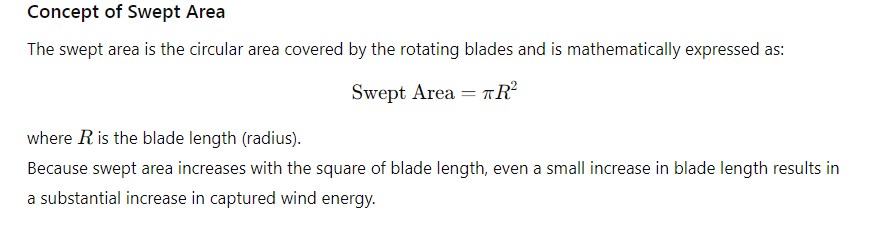

4. Blade Length and Swept Area

Blade length directly influences the swept area of the rotor, which determines how much wind energy can be captured. Longer blades increase energy output but also add mechanical loads. Designers balance blade length with material strength and turbine capacity to achieve optimal performance.

Blade length and swept area are two of the most influential factors determining the power output of a wind turbine. They define how much wind energy a turbine can intercept and directly affect efficiency, structural design, and overall system performance.

Understanding Blade Length

Blade length refers to the distance from the hub center to the blade tip. Longer blades allow the turbine to reach higher wind speeds found at greater heights and capture energy from a larger volume of moving air. As blade length increases, the turbine’s ability to extract energy improves significantly, especially in low to moderate wind regions.

Impact on Power Generation

Wind power output is directly proportional to the swept area. A turbine with longer blades can produce more electricity without increasing wind speed. This makes blade length optimization one of the most effective methods for improving turbine output and reducing the cost per unit of electricity.

Aerodynamic Efficiency Considerations

As blade length increases, maintaining aerodynamic efficiency becomes more challenging. Designers must ensure smooth airflow, proper twist, and optimal airfoil profiles along the extended blade to prevent losses due to turbulence or stall.

Structural and Mechanical Challenges

Longer blades experience higher bending moments, gravitational loads, and centrifugal forces. Advanced composite materials and structural reinforcement techniques are required to maintain blade strength while keeping weight low. Excessive blade mass can reduce efficiency and increase maintenance costs.

Effect on Low-Wind Performance

Large swept areas are especially beneficial in regions with low wind speeds. Turbines with long blades can generate usable power even when wind speeds are modest, improving capacity factor and energy reliability.

Transportation and Installation Constraints

Increasing blade length introduces logistical challenges such as transportation, installation, and site accessibility. These factors often influence the maximum practical blade size for a given project location.

Noise and Environmental Considerations

Longer blades move faster at the tips, potentially increasing aerodynamic noise. Designers use tapered tips and advanced blade shapes to control noise levels while maximizing energy capture.

Blade length and swept area are central to wind turbine performance and economics. By carefully optimizing blade size and swept area, engineers can significantly enhance energy production while balancing structural, environmental, and logistical constraints.

Tip Speed Ratio (TSR)

The tip speed ratio is the relationship between blade tip speed and wind speed. Efficient turbines operate within a specific TSR range, ensuring maximum energy extraction without excessive noise or mechanical stress. Blade geometry is optimized to maintain this ideal ratio.

The Tip Speed Ratio (TSR) is a key performance parameter in wind turbine operation that defines the relationship between the rotational speed of a turbine blade and the speed of the incoming wind. It plays a crucial role in determining how efficiently a wind turbine converts wind energy into mechanical power.

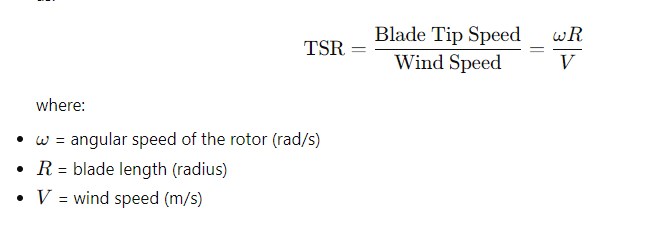

Definition of Tip Speed Ratio

Tip Speed Ratio is the ratio of the linear speed of the blade tip to the free-stream wind speed. It is expressed as:

Physical Meaning of TSR

TSR indicates how fast the blade tip moves relative to the wind. A higher TSR means the blade tip travels much faster than the wind, while a lower TSR indicates slower blade rotation. The correct balance ensures optimal interaction between the blade airfoil and airflow.

Optimal TSR and Turbine Efficiency

Each wind turbine design has an optimal TSR at which power extraction is maximized. At this point, aerodynamic forces generate maximum lift with minimal drag. Operating below or above this optimal TSR reduces efficiency due to poor airflow interaction or excessive aerodynamic losses.

TSR and Blade Design

Blade shape, number of blades, and airfoil profile are closely linked to TSR. Turbines with fewer blades typically operate at higher TSRs, while turbines with more blades operate at lower TSRs. Designers select TSR values that balance energy capture, structural loads, and noise levels.

Low TSR Operation

At low TSR, the blades move slowly compared to the wind. This causes inefficient energy extraction, increased drag, and potential airflow separation. The turbine may struggle to start or produce meaningful power.

High TSR Operation

At very high TSR, the blade tips move extremely fast, increasing aerodynamic noise, mechanical stress, and drag losses. Excessive TSR can also reduce power output and cause material fatigue over time.

Role of TSR in Turbine Control

Modern wind turbines continuously adjust rotor speed and blade pitch to maintain an optimal TSR across varying wind conditions. This dynamic control improves efficiency, reduces mechanical stress, and ensures stable power output.

Impact on Noise and Structural Loads

TSR influences blade tip noise and centrifugal forces. Higher TSR values increase noise emissions and structural loads, making TSR selection an important factor in turbine placement and environmental compliance.

Tip Speed Ratio is a fundamental parameter that links blade motion with wind behavior. By operating at an optimal TSR, wind turbines achieve maximum efficiency, reduced noise, and longer service life, making TSR a critical consideration in turbine design and operation.

Stall and Pitch Control Considerations

Blade design incorporates methods to control aerodynamic stall at high wind speeds. Pitch-controlled blades can adjust their angle to regulate lift and power output, preventing damage during extreme conditions and improving overall turbine safety.

Stall and pitch control are essential mechanisms used in wind turbines to regulate power output, maintain aerodynamic efficiency, and protect the turbine from excessive mechanical loads. These control strategies manage how the blades interact with wind under varying speed conditions.

Understanding Aerodynamic Stall

Aerodynamic stall occurs when the angle of attack of the blade exceeds a critical limit, causing airflow to separate from the blade surface. When stall happens, lift decreases sharply while drag increases, leading to reduced power generation and increased structural stress. Stall is not always undesirable; in some turbine designs, it is intentionally used as a control mechanism.

Stall-Controlled Wind Turbines

In stall-controlled turbines, blades are fixed and designed to naturally stall at high wind speeds. As wind speed increases beyond the rated value, the blades experience stall, limiting lift and preventing further power increase. This passive control method is simple and reliable but offers less precise regulation and can introduce higher mechanical loads and noise.

Pitch-Controlled Wind Turbines

Pitch control involves actively adjusting the angle of the blades using mechanical or hydraulic systems. By changing the blade pitch, the turbine can optimize lift at low wind speeds and reduce aerodynamic forces at high wind speeds. Pitch-controlled turbines offer superior efficiency, smoother operation, and better protection against extreme wind conditions.

Comparison of Stall and Pitch Control

Stall control relies on blade geometry and airflow behavior, while pitch control uses active adjustment. Pitch-controlled systems are more complex but provide better control over power output, load reduction, and operational flexibility. Stall-controlled systems are simpler but less adaptable to changing wind conditions.

Impact on Power Regulation

Pitch control allows turbines to maintain rated power output across a wide range of wind speeds. By feathering the blades (turning them out of the wind), turbines can safely operate or shut down during storms. Stall control, in contrast, offers limited power regulation and is more dependent on wind characteristics.

Structural and Fatigue Considerations

Uncontrolled stall can lead to vibration and fatigue damage over time. Pitch control helps reduce cyclic loading on blades, hub, and tower by smoothing aerodynamic forces, thereby extending the lifespan of turbine components.

Safety and Reliability

Pitch systems play a critical role in turbine safety. In emergency conditions, blades can be pitched to a neutral position to rapidly reduce rotor speed. This level of control enhances reliability and reduces the risk of mechanical failure.

Stall and pitch control are vital for managing aerodynamic forces and ensuring efficient turbine operation. While stall control offers simplicity, pitch control provides greater efficiency, safety, and adaptability, making it the preferred choice for modern wind turbines.

Material and Surface Finish Effects

Blade materials and surface smoothness significantly affect aerodynamic performance. Smooth surfaces reduce drag, while advanced composite materials offer high strength-to-weight ratios, enabling longer and more efficient blades.

Effective aerodynamics and blade design are essential for maximizing wind turbine efficiency, durability, and energy output. By carefully optimizing airfoil shape, blade geometry, and control mechanisms, modern wind turbines can operate closer to their theoretical performance limits while maintaining structural integrity and reliability.